- 15 Квітня 2013

- 1355

- Прокоментуй!

For many years, the Russian political elite have tried to influence the development of the Ukrainian-Jewish relations. The two people’s mutual understanding created a plethora of problems for Moscow. The outbreak of the Civil War in the Russian Empire had transformed the ‘Jewish question’ from a cultural-economic dimension into a geopolitical one. From the first days of the revolution, a significant part of the the Jewish population supported the Ukrainians’ liberation efforts. The Jewish organizations in Kyiv, Odesa, Katerynoslav, Kharkiv, and other cities, had recognized the Central Rada the only legal authority. The All-Ukrainian Rabbi Congress, which took place in Odessa in 1918, took a decision to impose a ‘herem’ (condemnation) on those Jews, which were aiding the Ukrainian republic’s enemies. Agreement between the Ukrainians and Jews gave a significant boost to the Ukrainian independence campaigners’ positions, which would be a decisive blow to Russia’s existence within its pre-revolutionary borders. Thus, every Russian government (Bolshevik or White) was interested in pulling the Jews across to their side, in the war against Ukrainians. In order to put that concept to life, the Russians launched a massive propaganda effort, which worked its way into creating the image of the ‘Ukrainian pogrom-maker’.

Both the White and the Red imperialists found it very convenient to paint the Ukrainians political struggle as an eternal pogrom, roistering and anarchist hell. The image of the Ukrainian National Republic’s regular army as a gang of anti-Semite rapists, would raise any Russian occupation to a ‘salvation of mankind’. Despite the fact that even modern Russian historians recognize both the Red and the Volunteer (White) armies being behind the pogroms in Ukraine, the Russians have managed to ‘point all fingers’ at the Ukrainians.

Already in modern times, the Kremlin is making all the efforts to support its own historiography: and independent Ukraine is a synonym of holocaust; the Jews had nothing to do with the independentists; the Ukrainian armies ‘did not accept Jews’, since the very Ukrainian army is a gang of anti-Semites and murderers. That attitude from Ukraine’s northern neighbour not only creates a negative image of Ukraine, but also isolates our country from the international community.

Probably the best way to defeat those stereotypes is collecting and spreading information about the Jews’ struggle in the Ukrainian National Republic’s Army. Afterall, one of the anti-Ukrainian propaganda’s pillars is the denial of the Jews’ part in the armed struggle for Ukraine’s independence. So, were there really Jews amongst the Petlurists?

Cossacks and officers of non-Ukrainian origin in the Army of the UNR were not a rarity. Their names were not loudly shouted around, saying ‘Look, there are Russians, Georgians, Jews, who are fighting with us!’. There was a simple explanation to that. The turbulent 1917 may have brought to Ukraine a double revolution – a national and a social one, however, it was that year when political Ukrainianness was born. Signifying russified Ukrainians, or people of other ethnicities that joined the service of the new state in March 1917, the term ‘Martovski ukrayintsi’ (‘March Ukrainians’) appeared.

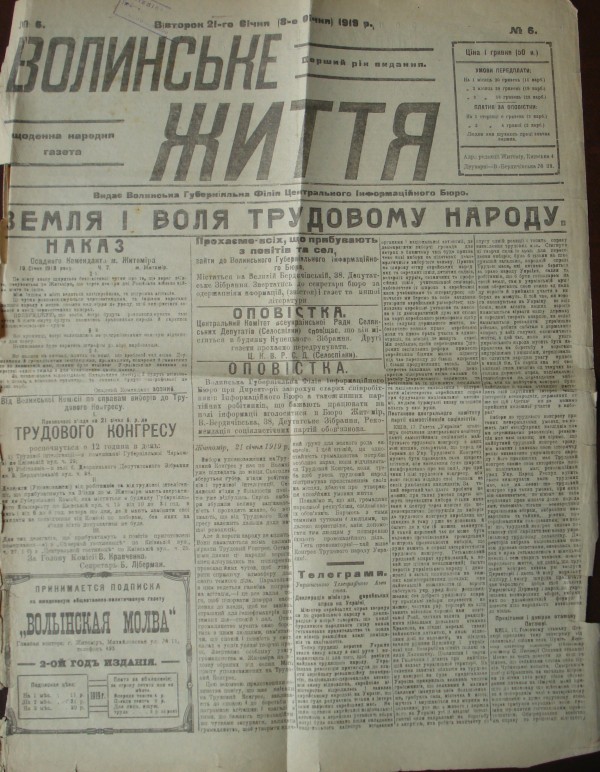

Looking through the UNR’s archives or the periodicals dating from the period of the Bolshevik-Ukrainian war, at times one can come across lists of mobilized Cossacks, or fallen soldiers. These lists feature surnames, which are highly atypical of Ukrainian. For example, the front-line newspaper ‘Ukrayinsky Kozak’ (‘The Ukrainian Cossack’) published ‘Lists of fallen Cossacks and officers’. After heavy fighting between the UNR Army and the Bolsheviks over the Vapniarka railway station, the last column of ‘Ukrayinsky Kozak’ featured the lists from the VII Blue Regiment. Amongst the tens of dead are, for instance, Cossack Semen Pashchenko from the town of Pavoloch near Kyiv, Cossack Pavlo Chumak from the village of Radivonivka near Katerynoslav (modern Dnipropetrovsk), Cossack Semen Kramarenko from the village of Pyvtsi near Kyiv, Cossack Schmul Zibelmann from the village of Muksha in Podolia.

Ailing from Podolia was another Ukrainian warrior, who, unlike Schmul, earned widespread recognition in the military. It was captain Semen Samuyilovych Jackerson. Semen came from a Jewish bourgeoise family from Vinnytsia. He decided to get his military education in Odesa, where many of his fellow Jews lived. Thus, in 1917, 20 year-old Jackerson graduated from artillery school, gaining the rank of ensign. He voluntarily enlisted into the Odesa Haydamak brigade of the army of the Central Rada. Partook in urban warfare against the Bolsheviks in Odesa.

The Ukrainian Jew becomes a haydamaka. Some may find it ridiculous, but fate tied the young man’s fate not only to the haydamakas, but also with the very capital of the historical phenomenon of the haydamakas – the city of Uman. During the period of Skoropadsky’s Hetmanate, Jackerson served at the office of the Uman Povit military head. During the uprising against His Majesty, just as many other Ukrainian officers, he sides with the Republicans. He then joins the 1st Active Volodymyr Vynnychenko Regiment of the Dyrektoria’s army. On January 23, 1919, he was injured during fighting near the Polissia town of Dubrovytsia, returning to his regiment after treatment, with the remainings of which, on May 24 1919, he adjoined the 8th Black Sea Regiment of the 3rd (later – Iron) Division of the Active Army of the UNR. On July 18, 1919, he took party in heavy fighting over the city of Komarhorod, where he was injured. Despite a second injury, he Jackerson did not leave the military, and soon returned to the front line. He then served in the Border Guard Corps of the UNR. During the joint Polish-Ukrainian advance towards Kyiv, in 1920, he fought in the 6th Auxiliary Artillery Unit, and the artillery unit of the 1st Machinegun Division of the UNR Army.

After the end of the War of Independence, together with the UNR Army he ended up on Polish territory, where he resided for 20 years. During emigration, he stuck with the Ukrainian political camp. The last mention of Jackerson from the artillery is his successful completion of the Hydrotechnical Department of the Ukrainian Economic Academy in Podebrady in 1927.

The Ukrainian poet Leonid Poltava dedicated captain Jackerson a poem. In the epigraph, he placed the following words: “Of the Jew S. Jackerson – captain of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic. Written under the impression of a story from New York by the poet and essayist Yevhen Malaniuk – captain of the Army of the UNR”.

Is this a dream? –

Jackerson!

Jackerson is Napoleon..

Who’s going to run

To warm homes, gowns,

Into vests and boots,

Into the glory of the old days –

And the warm evenings?

Perhaps some will.. perhaps it’s a dream –

But not Sioma Jackerson.

After Ukraine’s defeat in the First Liberation Struggle and the coming of the times of ‘balancing the accounts’ with political opponents, quite a few Jews were targeted by the Soviet penal authorities. Oftentimes, repressions against the Jews were carried out by their fellow ones. Amongst those who felt the effect of the red repressions machine, were captains Vitaly Abramovych (a native of Volhynia), Isaak Hodin and Judas Horovenko (natives of Kyiv), Pavlo Goldman and Ippolyt Hoffmann (natives of Poltava), Yefym Goldman-Sokolov (native of Mozyr) and Lev Apte (native of Saint Petersburt), and many others.

Often, one can hear that the roots of anti-Semitism lie in the economical and social dimensions. Jews practiced usury, they owned large financial capital, which, it was said, caused tension with the Ukrainian peasants and townsfolk. Yet, in the history of the UNR’s struggle for independence there are plenty of examples of Jews supporting the newly-established army financially. For instance, on April 9, 1919, the Jewish Community Council of Zdolbuniv considered the question of financial support for the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic. It should be said, that the latter, at that time, was in an extremely dramatic state: it was constantly retreating westward. The army suffered from severe lackings in weapons and ammunition. Thus, Zdolbuniv’s Jews carried out an extraordinary gathering of funds. In one day, 20 000 karbovantsi were donated, which were transferred to the Zdolbuniv comendant ‘for the benefit of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic’. Undoubtedly, this single episode did not change the material state of the UNR Army, however, the multitude of such events would lay the ground for renewed Jewish-Ukrainian relations.

Ukraine’s Jews were not a homogenous community in the 20th century. Their representatives could be found in the Ukrainian, but also in the Bolshevik and White political camps. Oftentimes, it was hard for the Jews themselves to judge their ancestors’ actions. Afterall, between 1917 and 1921 the idea of a Jewish state was only seeking ways towards becoming reality. While and independent Ukraine became a reality already in that same period. And it did not happen without the above mentioned individuals.

They say that history should teach. If so, then Zibelmann, Jackerson and many other of our warriors taught us to value those, who work and fight in the name of Ukraine, and not those who speak in its name.

Author: Pavlo Podobied, translated into English by ‘Heroyika’ volunteer Alex Miroshnychenko

Залишити відповідь